Combining event sourcing and stateful systems

Written on 2020-04-14In this two-part series, my colleague Freek and I will discuss the architecture of a project we're working on. We will share our insights and answers to problems we encountered along the way. This part will be about the design of the system, while Freek's part will look at the concrete implementation.

Let's set the scene.

This project is one of the larger ones we've worked on. In the end it will serve hundreds of thousands of users, handle large amounts of financial transactions and standalone tenant-specific installations will need to be created on the fly.

One key requirement is that the product ordering flow — the core of the business — can be easily reported on, as well as tracked throughout history.

Besides this front-facing client process, there's also a complex admin panel to manage products. Within this context, there's little to no need for reporting or tracking history of the admin activities; the main goal here is to have an easy-to-use product management system.

I hope you understand that I deliberately am keeping these terms a little vague because obviously this isn't an open-source project, though I think the concepts of "product management" and "orders" is clear enough for you to understand the design decisions we've made.

Let’s first discuss an approach of how to design this system based on my Laravel beyond CRUD series.

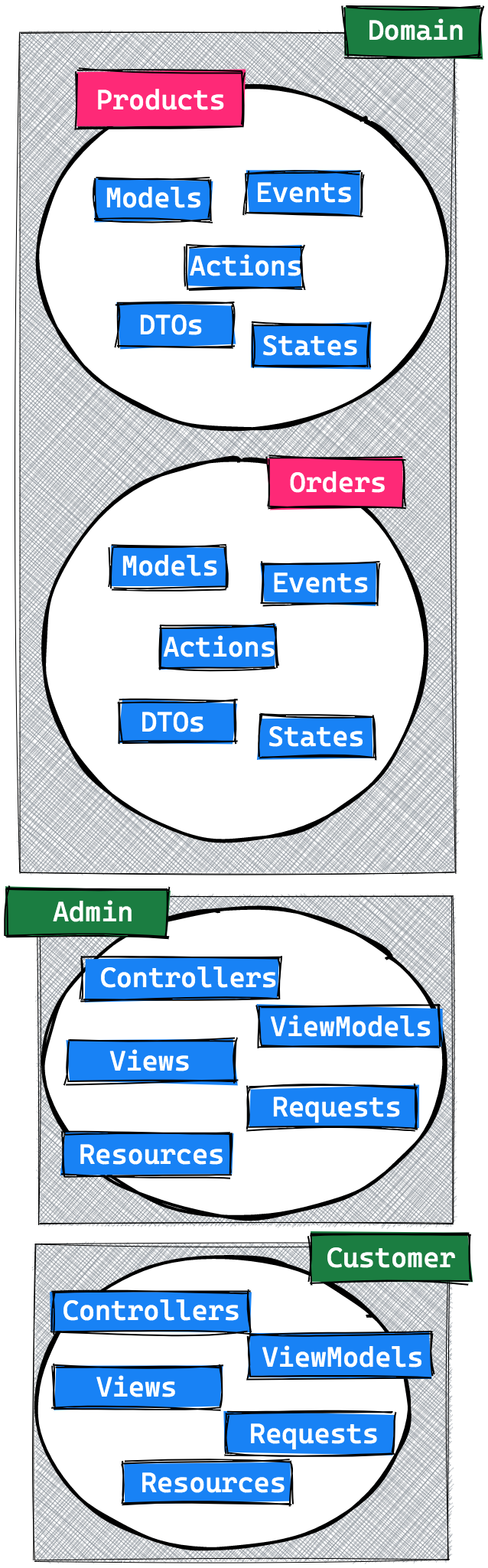

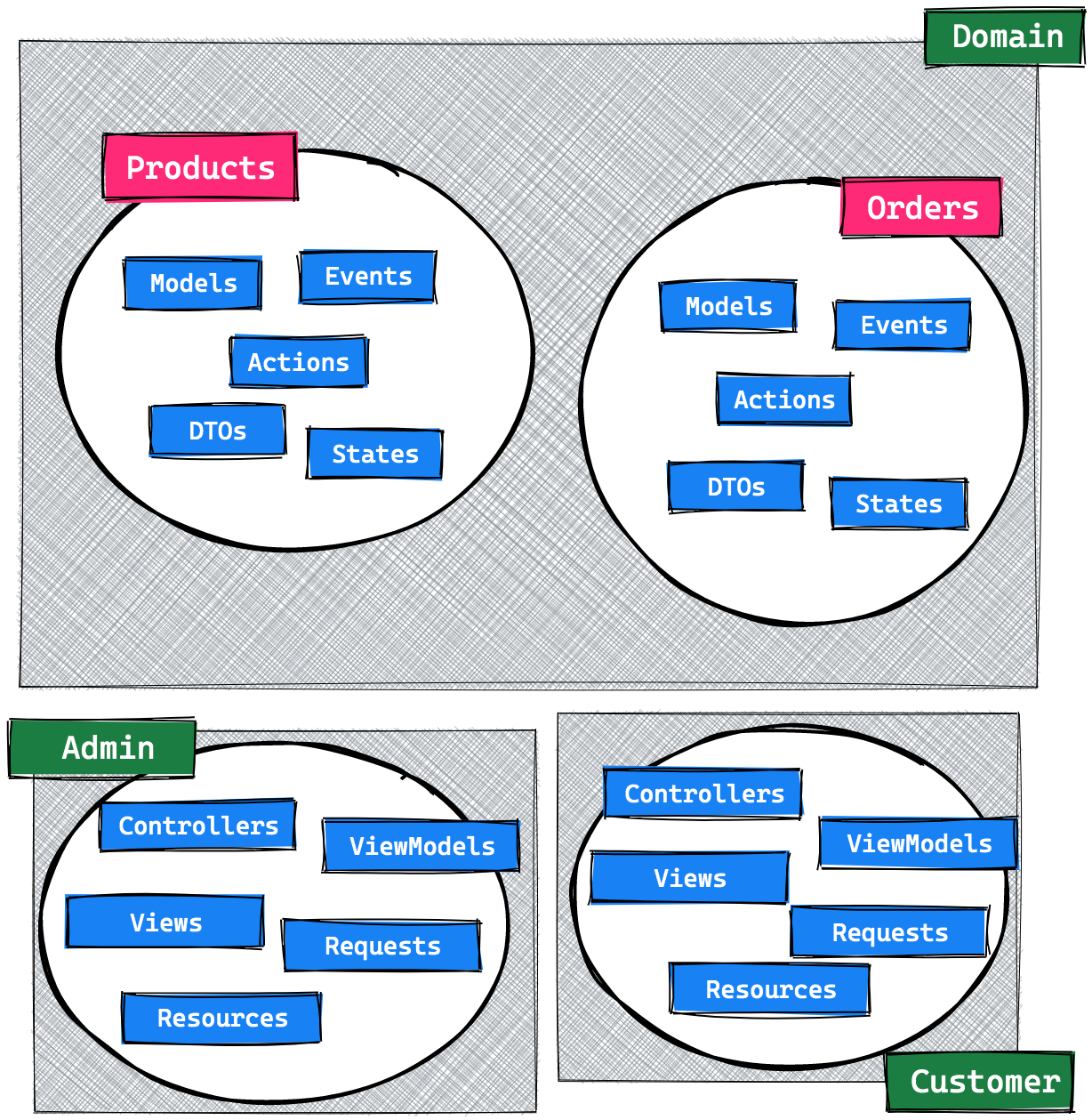

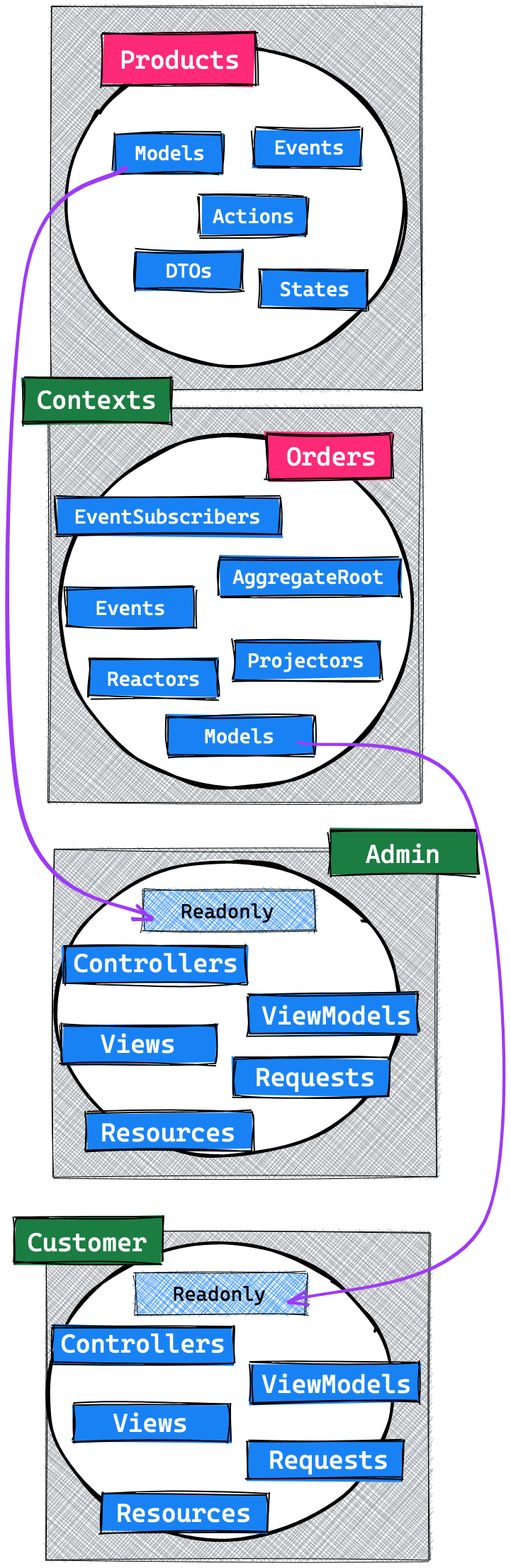

In such a system there would probably be two domain groups: Product and Order, and two applications making use of both these domains: an AdminApplication and a CustomerApplication.

A simplified version would look something like this:

Having used this architecture successfully in previous projects, we could simply rely on it and call it a day. There are a few downsides with it though, specifically for this new project: we have to keep in mind that reporting and historical tracking are key aspects of the ordering process. We want to treat them as such in our code, and not as a mere side effect.

For example: we could use our activity log package to keep track of "history messages" about what happened with an order. We could also start writing custom queries on the order and history tables to generate reports.

However, these solutions only work properly when they are minor side effects of the core business. In this case, they are not. So Freek and I were tasked with figuring out a design for this project that made reporting and historical tracking an easy-to-maintain and easy-to-use, core part of the application.

Naturally we looked at event sourcing, a wonderful and flexible solution that fulfills the above requirements. Nothing comes for free though: event sourcing requires quite a lot of extra code to be written in order to do otherwise simple things. Where you'd normally have simple CRUD actions manipulating data in the database, you now have to worry about dispatching events, handling them with projectors and reactors, whilst always keeping versioning in mind.

While it was clear that an event sourced system would solve many of the problems, it would also introduce lots of overhead, even in places where it wouldn't add any value.

Here's what I mean with that: if we decide to event source the Orders module, which relies on data from the Products module, we also need to event source that one, because otherwise we could end up with an invalid state. If Products weren't event sourced, and one was deleted, we couldn't rebuild the Orders state anymore, since it's missing information.

So either we event source everything, or find a solution for this problem.

Event source all the things?!

From playing around with event sourcing in some of our hobby projects, we were painfully aware that we shouldn't underestimate the complexity it adds. Furthermore, Greg Young stated that event sourcing a whole system is often a bad idea — he has a whole talk on misconceptions about event sourcing and is worth a watch!

It was clear to us that we did not want to event source the whole application; it simply wouldn't make sense to do so. The only alternative was to find a way to combine a stateful system, together with an event sourced system, but surprisingly, we couldn't find many resources on this topic.

Nevertheless, we did some labour intensive research, and managed to find an answer to our question. The answer didn't come from the event sourcing community though, but rather from well-established DDD practices: bounded contexts.

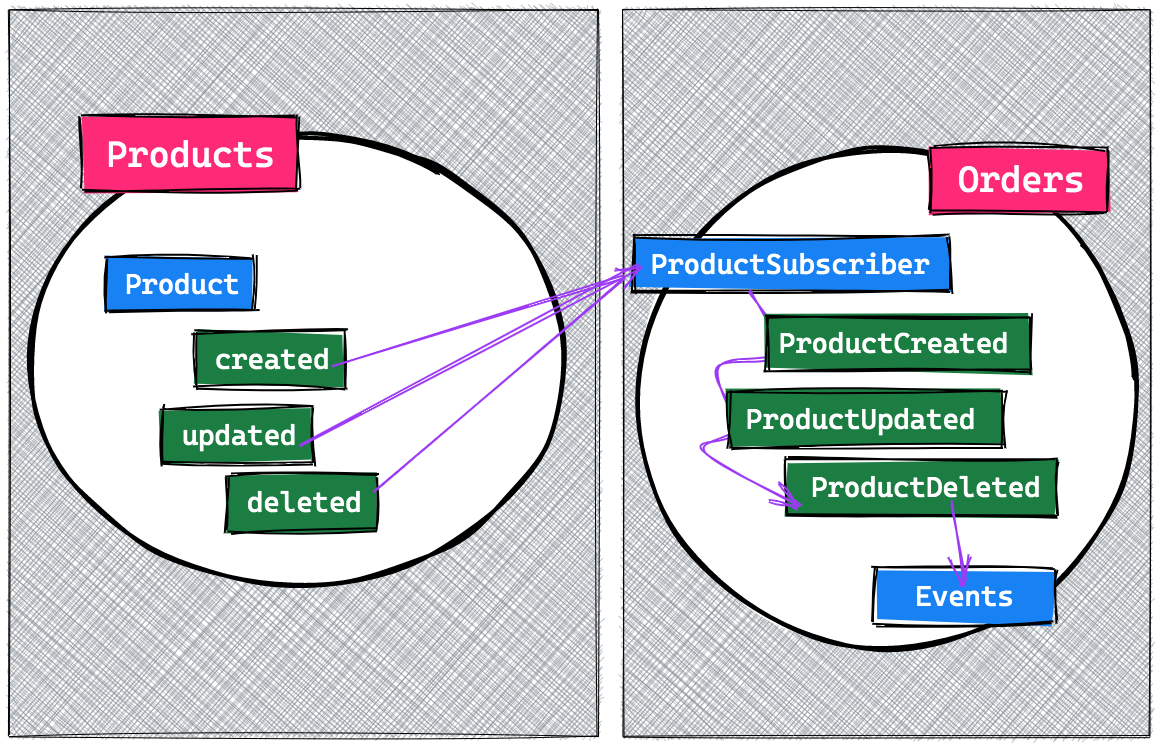

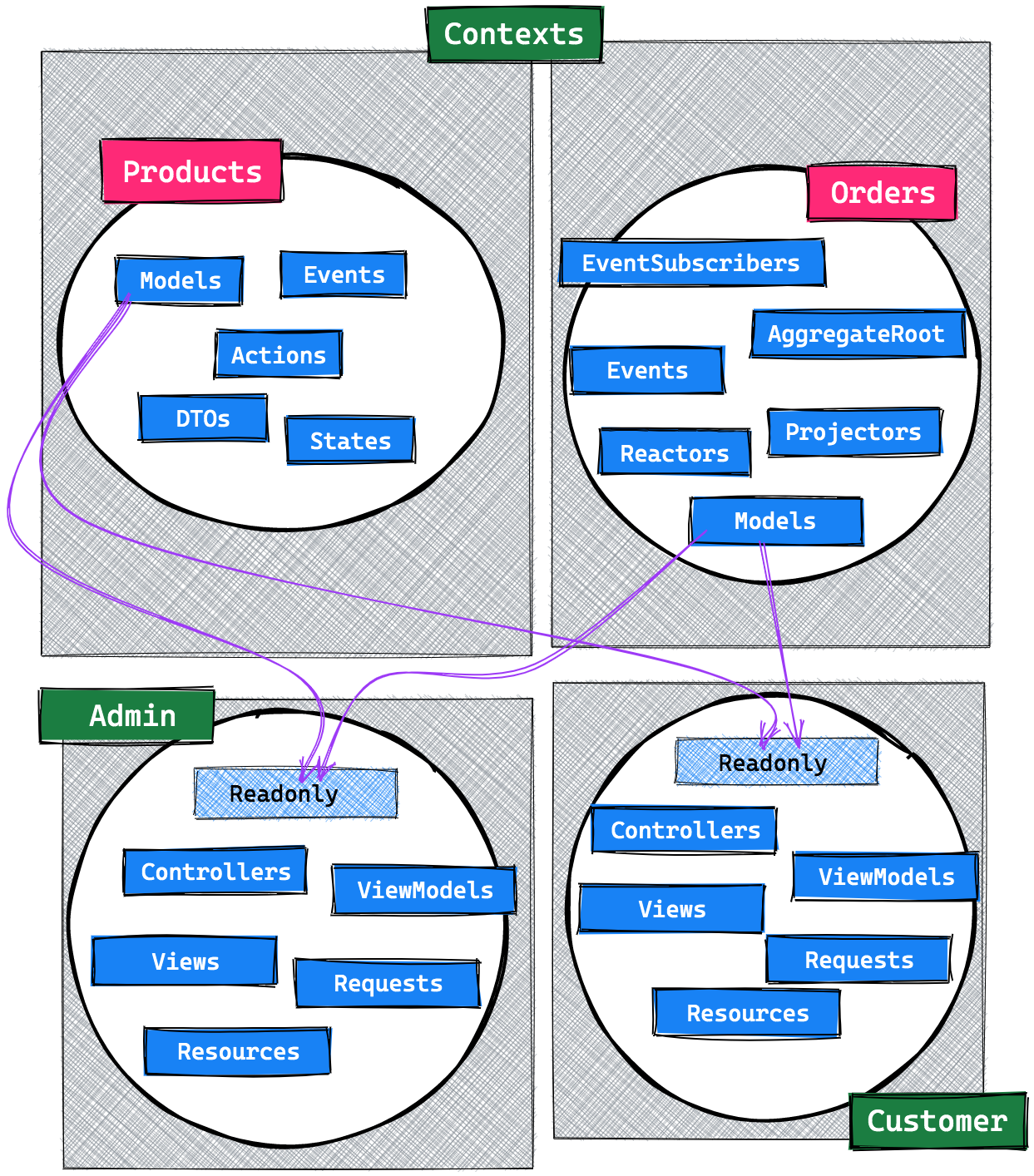

If we wanted the Products module to be an independent, stateful system, we had to clearly respect the boundaries between Products and Orders. Instead of one monolithic application, we would have to treat these two modules as two separate contexts — separate services, which were only allowed to speak with each other in such a way that it be could guaranteed the Order context would never end up in an invalid state.

If the Order context is built whereby it doesn't rely on the Product context directly, it wouldn't matter how that Product context was built.

When discussing this with Freek, I phrased it like this: think of Products as a separate service, accessed via a REST API. How would we guarantee our event sourced application would still work, even if the API goes offline, or makes changes to its data structure.

Obviously we wouldn't actually build an API to communicate between our services, since they would live within the same codebase on the same server. Still it was a good mindset to start designing the system.

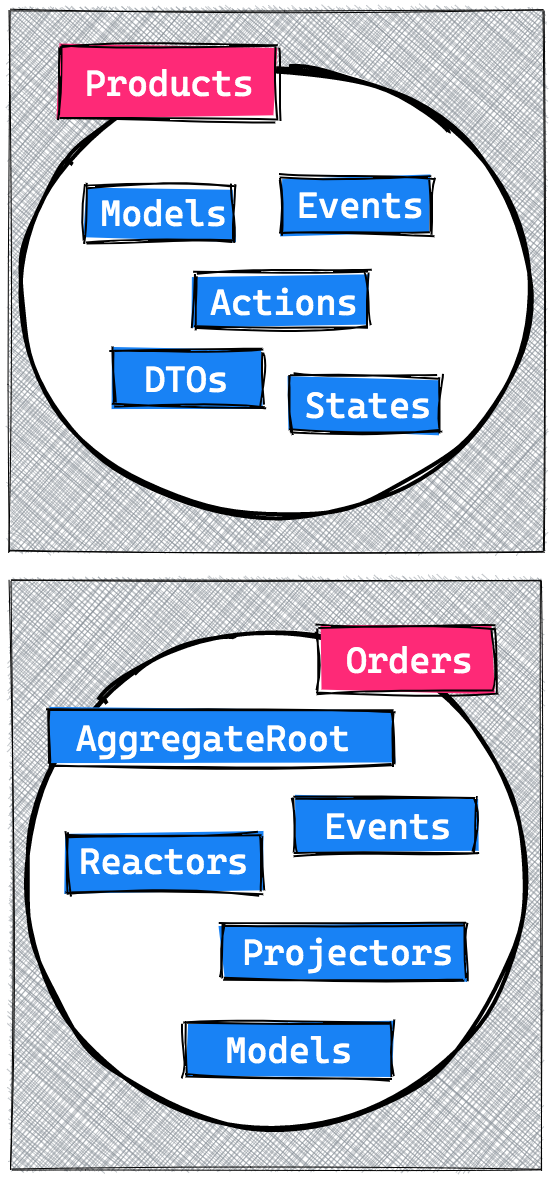

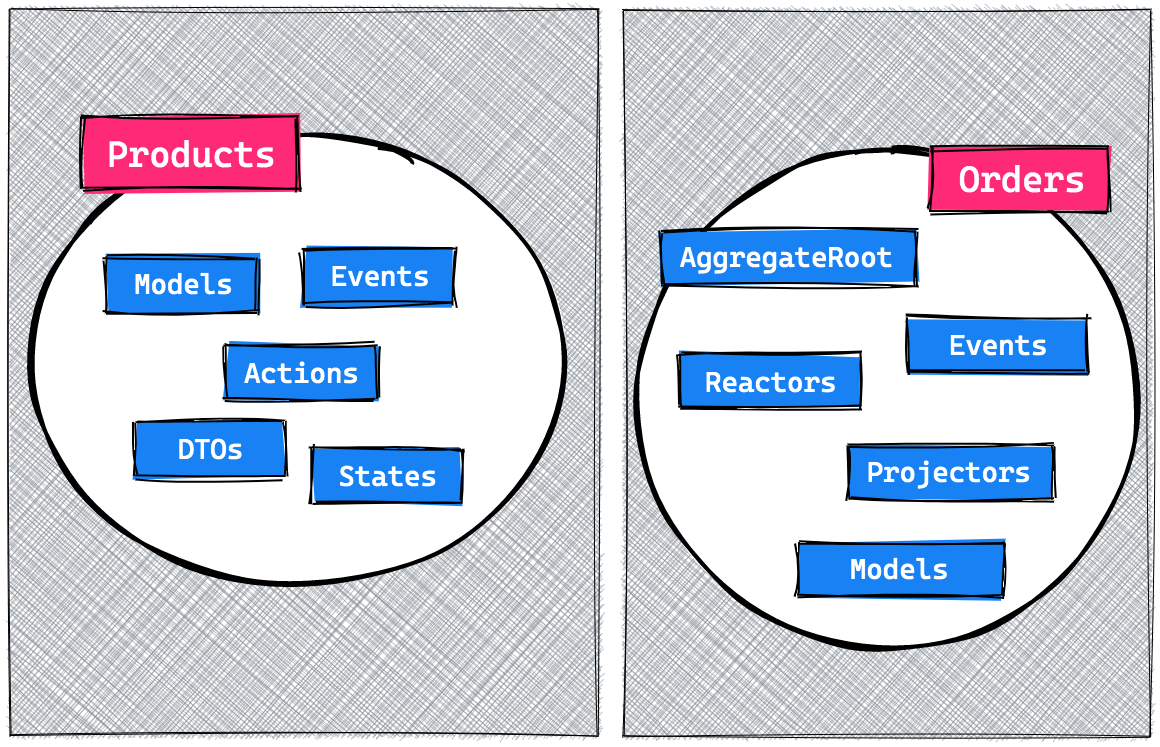

The boundary would look like this, where each service has its own internal design.

If you read my Laravel beyond CRUD series, you're already familiar with how the Product context works. There's nothing new going on over there. The Order context deserves a little more background information though.

Join over 14k subscribers on my mailing list: I write about PHP, programming, and keep you up to date about what's happening on this blog. You can subscribe by sending an email to brendt@stitcher.io.

Event source some parts

So let's look at the event sourced part. I assume you that if you're reading this post, you have at least an interest in event sourcing, so I won't explain everything in detail.

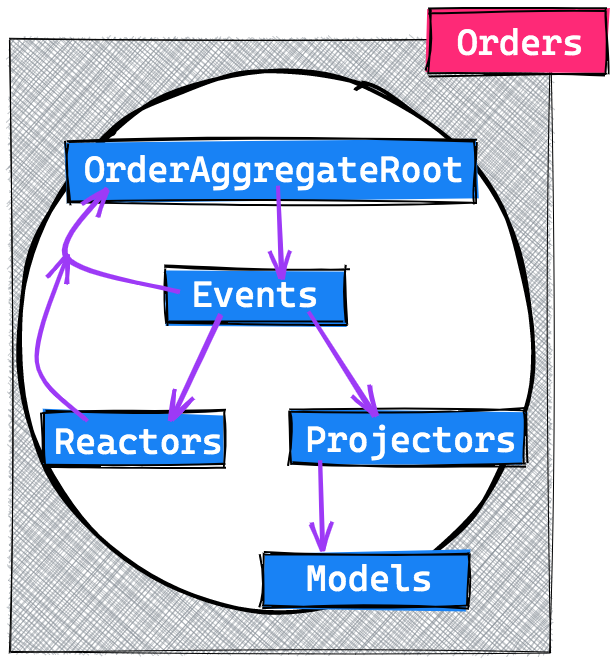

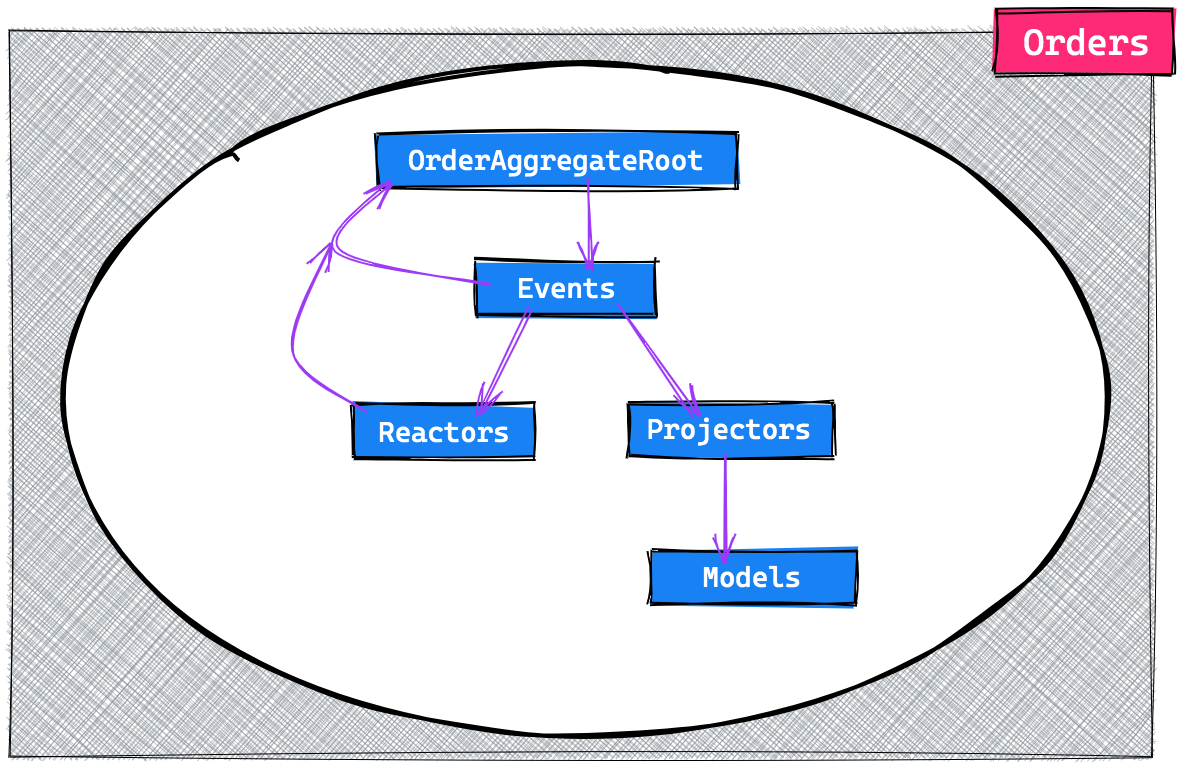

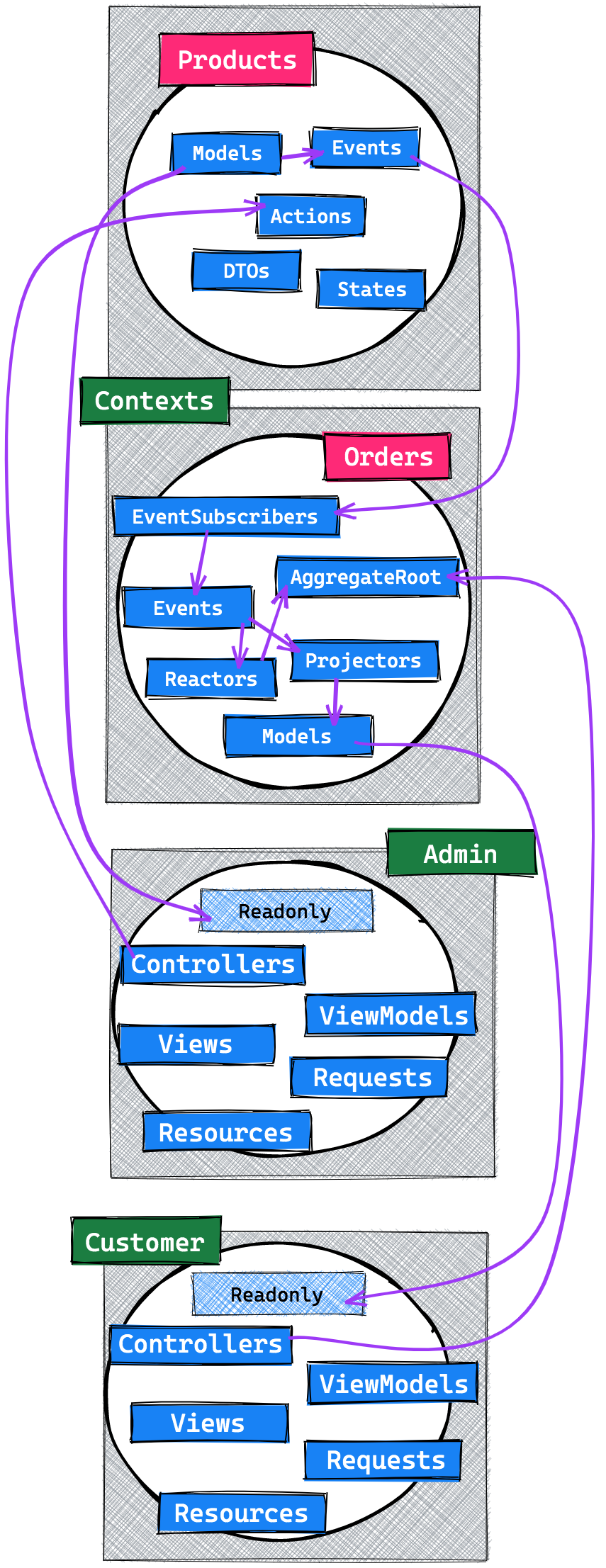

The OrderAggregateRoot will keep track of everything that happens within this context and will be the entry point for applications to talk with. It will also dispatch events, which are stored and propagated to all reactors and projectors.

Reactors will handle side effects which will never be replayed and projectors will make projections. In our case these are simple Laravel models. These models can be read from any other context, though they can only be written to from within projectors.

One design decision we made here was to not split our read and write models, for now we rely on a spoken and written convention that these models are only written to via their projectors. One example of such a projection model would be an Order.

The most important rule to remember is that the whole state of the Order context should be able to be rebuilt only from its stored events.

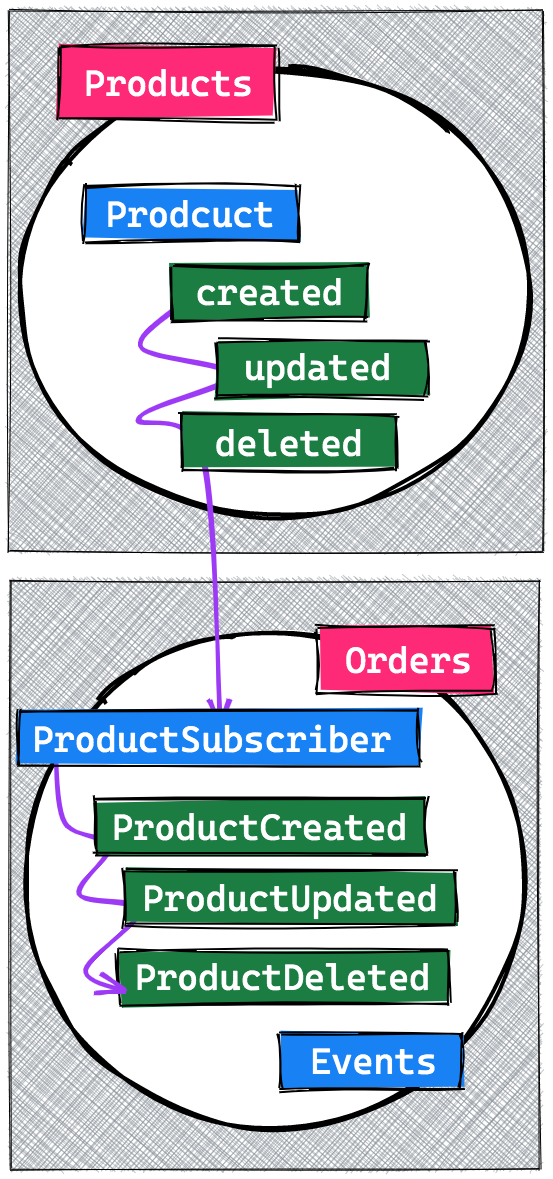

So how do we pull in data from other contexts? How can the Order context be notified when something happens within the Product context that's relevant to it? One thing is for sure: all relevant information regarding Products will need to be stored as events within the Order context; since within that context, events are the only source of truth.

To achieve this, we introduced a third kind of event listener. There already are projectors and reactors; now we add the concept of subscribers. These subscribers are allowed to listen to events from other contexts, and handle them accordingly within their current context. Most likely, they will almost always convert external events to internal, stored ones.

From the moment events are stored within the Order context, we can safely forget about any dependency on the Product context.

Some readers might think that we're duplicating data by copying events between these two contexts. We're of course storing an Orders specific event, based on when a Product was created, so yes, some data will be copied. There are, however, more benefits to this than you might think.

First of all: the Product context doesn't need to know anything about which other contexts will use its data. It doesn't have to take event versioning into account, because its events will never be stored. This allows us to work in the Product context as if it was any normal, stateful application, without the complexity event sourcing adds.

Second: there will be more than just the Order context that's event sourced, and all of these contexts can individually listen to relevant events triggered within the Product context.

And third: we don't have to store a full copy of the original Product events since each context can cherry-pick and store the data that's relevant for its own use case.

What about data migrations?

A new question arose.

Say this system has been in production for a year, and we decide to add a new context that's event sourced; one which also requires knowledge about the Product context. The original Product events weren't stored — because of the reasons listed above — so how can we build an initial state for our new context?

The answer is this: at the time of deployment, we'll have to read all product data, and send relevant events to the newly added context, based on the existing products. This one-time migration is an added cost, though it gives us the freedom to work within the Product context without ever having to worry about the outside. For this project that's a price worth paying.

Final integration

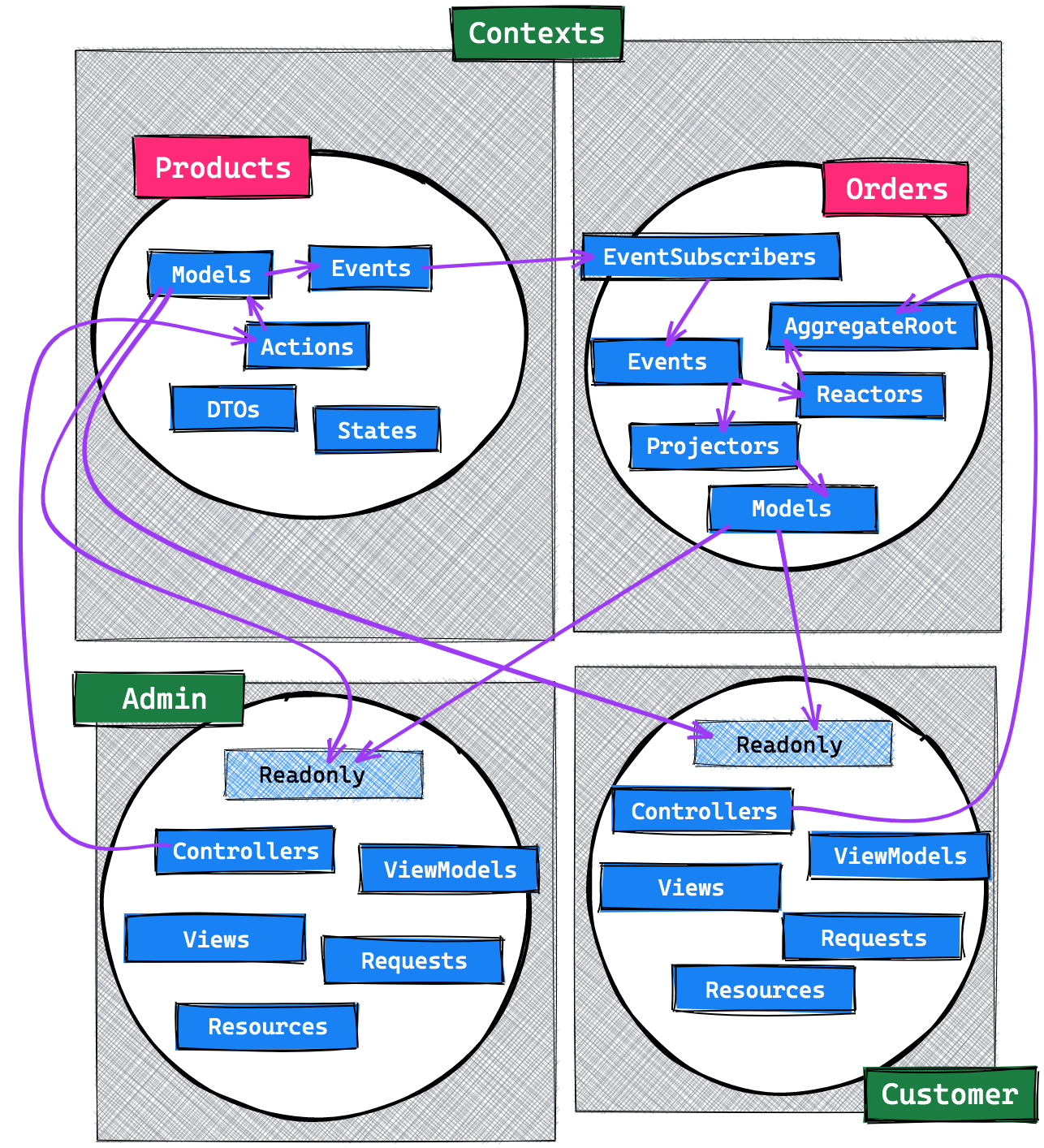

Finally we're able to consume data in our applications gathered from all contexts, by using readonly models. Again, in our case and as of now, these models are readonly by convention; we might change that in the future.

Communication from applications to the Product context is done like any normal stateful application would do. Communication between applications and event sourced contexts such as Orders is done via its aggregate root.

Now, here's a final overview. Some arrows are still missing from this diagram, but I hope that the relevant flow between and inside contexts and applications is clear.

The key in solving our problem was to look at DDD's bounded contexts. They describe strict boundaries within our codebase - ones that we cannot simply cross whenever we want. Sure this adds a layer of complexity, though it also adds the freedom to build each context whatever way we want, without having to worry about supporting others.

The final piece of the puzzle was to solely rely on events as a means of communication between contexts. Once again it adds a layer of complexity, but also a means of decoupling and flexibility.

Now it's time to take a deep dive into how we programmed this within a Laravel project. Here's my colleague Freek with part two.